The concept of modes in music have been a remarkable idea and compositional tool in music theory. While basic tonal concepts (major & minor) are on their own plenty efficacious in eliciting various emotional responses, I couldn’t help after a while but feel that they were rather limited, and I sought to read into other motifs that these could not portray.

Modes are one such tool that I discovered; an exceptional one at that, even. Although modal concepts are rather aged, used in Ancient Greece and the early Church, they’ve begun to be revamped in recent years by musicians attempting to add a little spice into their compositions without them inexplicably ascending towards jazz-hood.

In this post, I shall attempt to give an introductory overview to the modes and how they can be melded with tonal concepts for use in modern compositions. I shall take a structured approach to formalise certain ideas, but they should be thought of as recommendations rather than strict rules. I will not assume that the readers already know about modes, but at least have basic knowledge about major and natural minor scales, as well as chords.

Disclaimer: I have never taken any formal lessons on music theory and am purely self-taught. I may not be an expert on this field, hence my understanding may not be that developed.

Overview

- Scales vs Modes

- Scale

- Mode

- Chords

- Chord Construction

- Triads

- Seventh Chords

- Chord Nomenclature

- Forms

- Inversions

- Chord Progressions

- Scale Degrees

- Functional Harmony

- Modal Harmony

- Chord Construction

- Modern Modes

- Ionian

- Lydian

- Mixolydian

- Aeolian

- Dorian

- Phrygian

- Locrian

- Minor Scale Variants

- Harmonic Minor

- Melodic Minor

- Composition

- Modal Interchange & Modulation

- Modal Uncertainty

- Example

- Modal Hybrids

- Example

- Useful Links

Scales vs Modes

I have found that there is usually some confusion between the terms scales and modes. In this post, I shall follow the conventional definition as per their Wikipedia pages (see Scale and Mode). Loosely speaking, their definitions can be taken to mean the same thing and I may use them interchangeably. It might aid your understanding to think about scales and modes as akin to elements and isotopes in physics/chemistry.

Scale

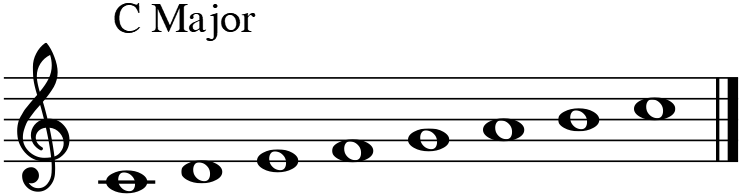

A scale is defined as a sequence of intervals (spacings) between successive keys. For the major scale, the sequence is W–W–H–W–W–W–H, where W stands for whole step or tone, and H stands for half step or semitone. For the natural minor scale, it is W–H–W–W–H–W–W. You can obtain the keys of a scale by assigning a key between any 2 intervals; usually the first key (the tonic). e.g. In B Minor, the tonic is B.

Scales can be categorised most broadly by the number of keys in the scale. Below are the common categories:

- Pentatonic Scale: Scales with 5 keys per octave. Commonly used in traditional Asian music.

- Hexatonic Scale: Scales with 6 keys per octave. Commonly used in blues.

- Heptatonic Scale: Scales with 7 keys per octave. Commonly used in popular music.

- Diatonic Scale: Heptatonic scales with 5 whole steps and 2 half steps, where the half steps are separated by 2 or 3 whole steps. The major and natural minor scales are diatonic scales.

- Octatonic Scale: Scales with 8 keys per octave. Commonly used in bebop.

- Chromatic Scale: Scale with 12 keys per octave. There is only 1 of this scale, used in jazz.

Necklace graphs (source) are really useful for visualising scales. These graphs are labelled with all 12 semitones in an octave and loops on itself. Below is a graph of the C Major scale where grey indicates the tonic and yellow indicates the notes in the scale:

In this graph, you can perform a transposition by rotating all names in either direction without moving the colours. e.g. Rotating the names of the C Major scale until E is at the tonic position is the same as transposing to E Major.

Mode

A mode is a scale, but with the added connotation of a relation with other scales formed by rotating the sequence (i.e. the modes of a scale are rotated versions of the scale). For lack of a better name, I will refer to this rotating action as mode shift. In this example, we will use the major scale.

- To rotate by 1, take the first element (W)–W–H–W–W–W–H and move it to the last position, which gives us a new scale: W–H–W–W–W–H–(W).

- To rotate by 5, take the first 5 elements (W–W–H–W–W)–W–H and move them to the last position, also giving a new scale: W–H–(W–W–H–W–W).

Note that interestingly, mode-shifting the major scale by 5 gives us the natural minor scale, and mode-shifting the natural minor scale by 2 gives us the major scale. Hence, the natural minor scale is a mode of the major scale and vice versa. Including itself, there are a total of 7 modes of the major scale, known as the Modern Modes.

In a necklace graph, you can perform a mode shift by rotating all colours in either direction without moving the names. e.g. Rotating the colours of the C Major scale until the colour originally at A moves to C is the same as mode-shifting to C Natural Minor.

For any scale, the number of modes is not always equal to the number of intervals, but will never exceed it. For example, the whole tone scale W–W–W–W–W–W comprises of 6 intervals but has only 1 mode, since the sequence is rotation-invariant.

Chords

Chord Construction

I shall first discuss about chords as they play a large role in compositions. Chords are simply collections of keys played simultaneously to provide a fuller sound than a key on its own. Perhaps you might have an understanding of chords that is more abstract than this definition, and please share it if you do, but this shall suffice for anyone new.

By convention, all keys in a scale are numbered relative to the key in its name. For example:

- In the C Major scale, C is the tonic/first, D is the second, E is the third, etc.

- In the C Minor scale, C is the tonic/first, D is the second, E♭ is the third, etc.

I shall use the C Major scale in my examples as it is easy to work with.

Most typically, chords are constructed by stacking notes from the root note in interval of thirds; a concept known as tertian harmony or informally, stacked thirds. There are other ways to construct chords by stacking in different intervals such as secundal harmony (seconds), quartal harmony (fourths), quintal harmony (fifths), etc. These are known as Chord Structures, and have different uses which will not be discussed in detail.

Triads

The most common chords are chords which consist of 3 notes, known as triads. In the C Major scale:

- To construct the chord starting on C, we would first include C, then include the third and fifth (third of the third) notes from C in the scale, which are E and G respectively. This gives us C E G.

- E is spaced 2 tones away from C, and is known as the major third of C.

- G is spaced 3½ tones away from C, and is known as the perfect fifth of C.

- Tonic + Major Third + Perfect Fifth = Major Triad

- Hence, the chord is C (C major).

- To construct the chord starting on D, we would first include D, then include the third and fifth notes from D in the scale, which are F and A respectively. This gives us D F A.

- F is spaced 1½ tones away from D, and is known as the minor third of D.

- Tonic + Minor Third + Perfect Fifth = Minor Triad

- Hence, the chord is Dm (D minor).

- To construct the chord starting on B, we would first include B, then include the third and fifth notes from B in the scale, which are D and F respectively. This gives us B D F.

- F is spaced 3 tones away from B, and is known as the diminished fifth of B.

- Tonic + Minor Third + Diminished Fifth = Diminished Triad

- Hence, the chord is Bo (B diminished).

All triads in major and natural minor will fall into one of the above categories.

Seventh Chords

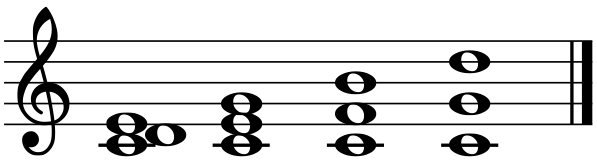

Certain chords stack an additional third on top of a triad to produce a fuller-sounding chord. These chords are known as seventh chords and consist of 4 notes. In the C Major scale:

- We can extend the triad C by including the seventh (third of the fifth), which is B. This gives us C E G B.

- B is spaced 5½ tones away from C, and is known as the major seventh.

- Tonic + Major Third + Perfect Fifth + Major Seventh = Major Seventh Chord

- Hence, the chord is CM7 (C major seven).

- We can extend the triad Dm by including the seventh, which is C. This gives us D F A C.

- C is spaced 5 tones away from D, and is known as the minor seventh.

- Tonic + Minor Third + Perfect Fifth + Minor Seventh = Minor Seventh Chord

- Hence, the chord is Dm7 (D minor seven).

- We can extend the triad G by including the seventh, which is F. This gives us G B D F.

- Tonic + Major Third + Perfect Fifth + Minor Seventh = Dominant Seventh Chord

- Hence, the chord is G7 (G seven or G dominant seven).

- We can extend the triad Bo by including the seventh, which is A. This gives us B D F A.

- Tonic + Minor Third + Diminished Fifth + Minor Seventh = Half-Diminished Seventh Chord

- Also known as a Half-Diminished Chord or Minor Seventh Flat Five Chord.

- Hence, the chord is Bø7 (B half-diminished seven), Bø (B half-diminished), or Bm7♭5 (B minor seven flat five). ø7 will be used here.

All seventh chords in major and natural minor will fall into one of the above categories. Also, the fifth does not serve a strong harmonic function in seventh chords, and may be omitted for a 3-note seventh chord. This is useful for sounds with distortion.

Chord Nomenclature

Forms

- Power Chords: Chords consisting of the tonic and fifth. Usually used for sounds with distortion.

- Triads: Chords consisting of the tonic, third and fifth. Also referred to as triad chords.

- Seventh Chords: Chords consisting of the tonic, third, fifth and seventh.

- Sixth Chords: Chords consisting of the tonic, third, fifth and sixth. Usually used as an alternative to seventh chords for less tension.

- Extended Chords: Chords that contain any further extensions with the ninth, eleventh or thirteenth. They have more inversions and are used heavily in jazz.

For chords with many keys, keys with weaker harmonic function can be omitted for a cleaner timbre, and is commonly done in practice.

Inversions

The bottommost (bass) key of a chord tends to have the most prominent sound of all the notes. As such, the tonic of the chord might not always be played on the bass. For any chord:

- If the bass key is the tonic, the chord is in its root position.

- If the bass key is the third, the chord is in its first inversion.

- If the bass key is the fifth, the chord is in its second inversion.

- If the bass key is the seventh, the chord is in its third inversion.

Chords in inversions are denoted as [chord name]/[bass key]. For example, C Major in first inversion is C/E. Each position has its own use in part writing, which I will not discuss in this post.

Chord Progressions

Here I will discuss the tonal concepts of scale degrees and functional harmony, then on modal harmony.

Scale Degrees

In tonal concepts, every note in the major or minor scale has a particular function. For this reason, Roman numerals are used to number each key in the scale, and each refers to the function of that key rather than the key itself. This function is known as the scale degree.

When composing, scale degrees are assigned in regular rhythmic intervals (e.g. 4 beats per scale degree for faster songs, 2 beats per scale degree for slower songs, etc.). The chord used in an interval depends largely on that interval’s scale degree. Upper case is used when the chord is a major chord, and lower case when the chord is a minor chord.

- Tonic: I in major, i in minor. The root of the scale. Can follow with any other scale degree.

- Supertonic: ii in major, II in minor. Resolves strongly to dominant.

- Mediant: iii in major and III in minor. A stable key in the scale. Resolves to submediant.

- Subdominant: IV in major, iv in minor. Resolves to dominant. Can follow with supertonic for greater effect.

- Dominant: V in major & minor. Resolves very strongly to tonic. Can follow with leading tone for greater effect.

- Submediant: vi in major, VI in minor. A very stable key in the scale. Can resolve to supertonic or subdominant, or used for deceptive cadences.

- Subtonic: ♭VII in minor only. Resolves to mediant.

- Leading Tone: viio in major & minor. Resolves most strongly to tonic.

Functional Harmony

Chord progressions in the major and natural minor keys usually follow functional harmony. The general idea behind functional harmony is the idea of resolving downwards in fifths. There is a mathematical theory behind consonance, dissonance and resolution explaining why fifths make this work, which I discuss in The Mathematics of Music. Functional harmony encourages the following progressions:

Although these ideas are mainly used only in the major and minor scales, the ideas of dissonances and resolutions are very useful even when composing with modes.

Modal Harmony

Every mode has its own characteristic chords which give it a signature vibe that distinguishes it from other modes. Modal chord progressions place emphasis on these specific chords that are not found in other modes, instead of strong resolutions like in functional harmony. Modal progressions generally do not have strong resolution tendencies.

If you are not composing/improvising in jazz, dominant seventh chords and diminished chords of modes other than Ionian are not recommended, as they attempt to resolve to another key than the tonic. If you are composing/improvising in jazz, then these “avoid chords” might be beneficial to help you establish a particular mode, and quartal harmony helps to reduce the strong resolution tendencies.

In each of the scales below, the chords and characteristic progressions will be listed. Focusing on those chords will give your compositions the modal vibe that is hardly found in tonal compositions.

Modern Modes

The following 7 modes are referred to as the modern modes, and can be derived from the major/natural minor scale. Here is a helpful video explaining the modern modes.

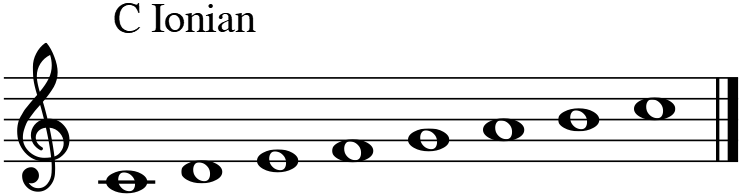

Ionian

Mood: Bright, Joyful

Intervals: W–W–H–W–W–W–H

Characteristic Keys: Major Third + Perfect Fourth + Major Seventh

Construction: I will start on familiar territory by introducing the simplest mode, the Ionian mode. Its key signature is the same as the major scale most are already familiar with. C Ionian is simply C Major, but with a strict emphasis on staying in the key.

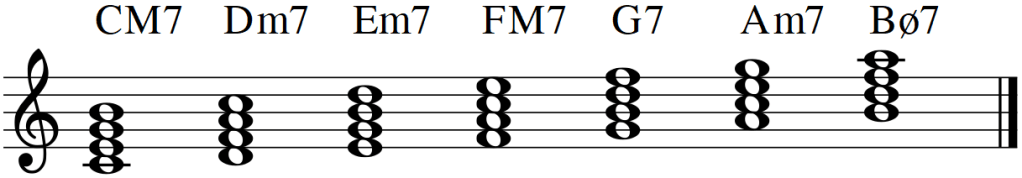

Chords: The chords in C Ionian are also the same as C Major, but fancier chords such as the Neapolitan Sixth, Augmented Sixth, etc. are not allowed as they contain notes outside the key. Only the following triads are allowed: C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am, Bo. The seventh chords are: CM7, Dm7, Em7, FM7, G7, Am7, Bø7.

Usage: As many already would know, Ionian has a painfully cliched happy vibe. Think Twinkle Twinkle Little Star or Mary Had a Little Lamb. Its rather boring sound is a consequence of two reasons: its high consonance and that so many songs use it that you’ve heard it ad nauseam. Do not avoid it though, as starting on Ionian and modulating/interchanging to another key/mode can generate pieces with exciting progressions.

Characteristic Progressions: I V I, I IV V I, I ii V I, I V viio I.

Lydian

Mood: Spacey, Dreamlike

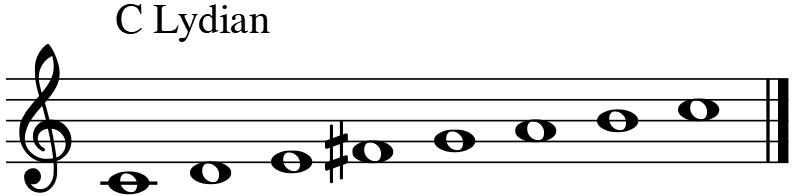

Intervals: W–W–W–H–W–W–H

Characteristic Keys: Major Third + Augmented Fourth

Construction: Consider the following notes from F to F in C Ionian: F, G, A, B, C, D, E, F. This is defined as F Lydian. We can transpose the root of F to C to obtain C Lydian. The Lydian mode is similar to the Ionian mode, but with an augmented fourth, i.e. C Lydian has the same notes as C Ionian except that F is replaced with F♯. This gives it a slightly brighter mood than Ionian.

Chords: The triads in C Lydian are: C, D, Em, F♯o, G, Am, Bm. The seventh chords are: CM7, D7, Em7, F♯ø7, GM7, Am7, Bm7.

The V chord should be avoided in progressions as it sounds overly resolved, being the root of the relative Ionian, but you can add the 6th to reduce the consonance or substitute it for the iii chord.

Usage: The theme song of The Jetsons, Back to the Future and The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess are some examples that use this mode. This might be useful for intermissions or atmospheric music.

Characteristic Progressions: I II I, I vii vi I.

Mixolydian

Mood: Spicy

Intervals: W–W–H–W–W–H–W

Characteristic Keys: Major Third + Minor Seventh

Construction: Consider the following notes from G to G in C Ionian: G, A, B, C, D, E, F, G. This is defined as G Mixolydian. We can transpose the root of G to C to obtain C Mixolydian. The Mixolydian mode is similar to the Ionian mode, but with a minor seventh, i.e. C Mixolydian has the same notes as C Ionian except that B is replaced with B♭. This gives it a slightly darker mood than Ionian.

Chords: The triads in C Mixolydian are: C, Dm, Eo, F, Gm, Am, B♭. The seventh chords are: C7, Dm7, Eø7, FM7, Gm7, Am7, B♭M7.

Usage: The Mixolydian mode is commonly used in blues and country. Coldplay – Clocks and David Bowie – Golden Years are some examples. The minor seventh in this mode is a very welcome twist to the Ionian mode. the minor seventh. An interesting fact is that this mode is the most consonant modern mode, but it likely sounds more interesting than Ionian as it has not been used nearly as much.

Characteristic Progressions: I v I, I IV v I, I ii v I.

Aeolian

Mood: Sullen, Solemn

Intervals: W–H–W–W–H–W–W

Characteristic Keys: Minor Third + Minor Sixth + Minor Seventh

Construction: Consider the following notes from A to A in C Ionian: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A. This is defined as A Aeolian. We can transpose the root of A to C to obtain C Aeolian. This is the reason why A Minor has the same key signature as C Major.

The Aeolian mode is familiar territory too as it has the same key signature as the natural minor scale, although there are noticeable differences. Tonal concepts such as leading tone resolutions (major seventh → tonic) and tritone resolutions (tritone → perfect fifth) are absent in the Aeolian mode.

Chords: The triads in C Aeolian are: Cm, Do, E♭, Fm, Gm, A♭, B♭. The seventh chords are: Cm7, Dø7, E♭M7, Fm7, Gm7, A♭M7, B♭7. The following triads in C Minor are not allowed in C Aeolian: G, Bo.

The V, V7 or viio chord is used plentifully in the minor key as it has a strong resolution tendency towards the tonic (I). However, in the Aeolian mode, only the v, v7 or VII chord is allowed. As a result, VII is not typically used before I.

Usage: The Aeolian mode should have a familiar vibe as it is used frequently, but the inherent tension in this mode makes it much more palatable than Ionian. David Bowie – 1984 and Phil Collins – In the Air Tonight are some examples. The avoidance of strong resolutions lead to a generally persistent sombre vibe that is distinct from the natural minor scale.

Characteristic Progressions: i iv v i, i VI VII i.

Dorian

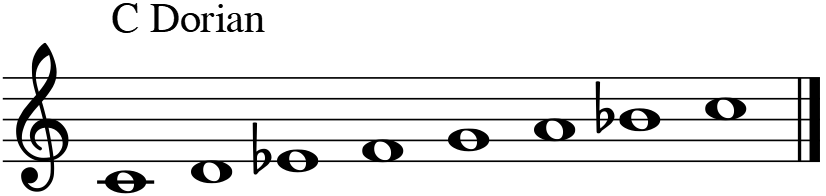

Mood: Hopeful, Refreshing

Intervals: W–H–W–W–W–H–W

Characteristic Keys: Minor Third + Major Sixth + Minor Seventh

Construction: Consider the following notes from D to D in C Ionian: D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D. This is defined as D Dorian. We can transpose the root of D to C to obtain C Dorian. The Dorian mode is similar to the Aeolian mode, but with a major sixth, i.e. C Dorian has the same notes as C Aeolian except that A♭ is replaced with A.

Chords: The triads in C Mixolydian are: Cm, Dm, E♭, F, Gm, Ao, B♭. The seventh chords are: Cm7, Dm7, E♭M7, F7, Gm7, Aø7, B♭M7.

Usage: The Dorian mode has a vibe that feels like a sunrise. Miles Davis – So What and Daft Punk – Get Lucky are some examples. The major sixth gives it a slightly brighter mood than Aeolian. This mode is sometimes used in superhero movies during the turnaround of a sticky situation.

Characteristic Progressions: i IV i, i IV v i, i ii i.

Phrygian

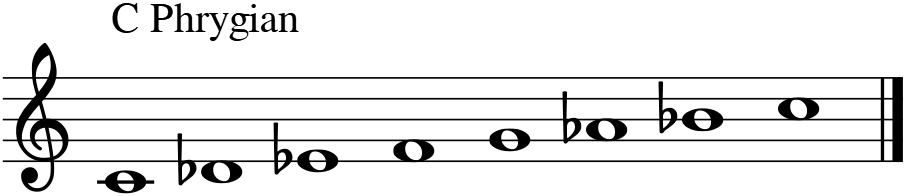

Mood: Dark, Exotic

Intervals: H–W–W–W–H–W–W

Characteristic Keys: Minor Second + Perfect Fifth

Construction: Consider the following notes from E to E in C Ionian: E, F, G, A, B, C, D, E. This is defined as E Phrygian. We can transpose the root of E to C to obtain C Phrygian. The Phrygian mode is similar to the Aeolian mode, but with a minor second, i.e. C Phrygian has the same notes as C Aeolian except that D is replaced with D♭. This gives it a slightly darker mood than Aeolian.

Chords: The triads in C Phrygian are: Cm, D♭, E♭, Fm, Go, A♭, B♭m. The seventh chords are: Cm7, D♭M7, E♭7, Fm7, Gø7, A♭M7, B♭m7.

Usage: The Phrygian mode has a somewhat Arabic vibe. Radiohead – Pyramid Song and Dick Dale & His Del Tones – Misirlou are some examples. The distinct sound that the minor second brings works very well in metal and hardcore.

Characteristic Progressions: i II i, i vii i.

Locrian

Mood: Mysterious, Unsettling

Intervals: H–W–W–H–W–W–W

Characteristic Keys: Diminished Fifth

Construction: Consider the following notes from B to B in C Ionian: B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B. This is defined as B Locrian. We can transpose the root of B to C to obtain C Locrian. The Locrian mode is the most distant from the familiar Ionian and Aeolian modes. It can be thought of as the Phrygian mode with a diminished fifth or the Lydian mode with an augmented tonic, but more commonly described as the former.

Chords: The triads in C Phrygian are: Co, D♭, E♭m, Fm, G♭, A♭, B♭m. The seventh chords are: Cø7, D♭M7, E♭m7, Fm7, G♭M7, A♭7, B♭m7.

Usage: The Locrian mode’s vibe is due to its diminished tonic chord, which does not sound resolved. If you need a stronger resolution, you can omit the diminished fifth or simply resolve in another mode. Almost all popular music are not composed in this scale.

You might have heard from some sources not to bother composing in Locrian, but do experiment with it anyway! You have to be careful about your melodic/harmonic progressions by finding out what sounds good and what doesn’t since it’s easy to go wrong. Occasionally performing a modal interchange from Phrygian to Locrian by flattening the fifth turns out to work very well for metal and hardcore, and can even sound better than pure Phrygian. You can also compose with Locrian as your primary scale; more details in the Modal Hybrids section below.

Characteristic Progressions: Almost any progression would be unique due to the diminished tonic chord. However, tertian harmony may not work very well for resolutions and so you may consider other chord structures.

Minor Scale Variants

Aside from the modern modes, there are also 2 non-diatonic scales that are commonly used for composition: harmonic minor and melodic minor. Each of these has 7 unique modes, but only the 2 scales will be listed here.

There are new chords that occur in the harmonic minor and melodic minor scales. The examples given are for C Harmonic Minor, which you can refer to below for the keys.

There is 1 new triad:

- Constructing a triad from E♭ gives us E♭ G B.

- B is spaced 4 tones away from E♭, and is known as the augmented fifth.

- Tonic + Major Third + Augmented Fifth = Augmented Triad

- Hence, the chord is E♭+ (E♭ augmented).

There are 3 new seventh chords:

- We can extend the triad Bo by including the seventh, which is A♭. This gives us B D F A♭.

- A♭ is spaced 4½ tones away from B, and is known as the diminished seventh.

- Tonic + Minor Third + Diminished Fifth + Diminished Seventh = Diminished Seventh Chord

- Also known as a Fully-Diminished Seventh Chord.

- Hence, the chord is Bo7 (B diminished seven or B fully-diminished seven).

- We can extend the triad E♭+ by including the seventh, which is D. This gives us E♭ G B D.

- Tonic + Major Third + Augmented Fifth + Major Seventh = Augmented Major Seventh Chord

- Hence, the chord is E♭+M7 (E♭ augmented major seven).

- Constructing a seventh chord from C gives us C E♭ G B.

- Tonic + Minor Third + Perfect Fifth + Major Seventh = Minor Major Seventh Chord

- Hence, the chord is CmM7 (C minor major seven).

An interesting property of diminished seventh chords is that the 3 inversions of Bo7 are respectively equivalent to Do7, Fo7, and A♭o7. This means that the bass key of a diminished seventh chord can be taken to be any of the 4 keys, giving it a natural ambiguity in its key. This makes these chords very useful for modulations to other keys. To be concise, this equivalence is enharmonic equivalence, which only applies to equal temperament systems. I will not discuss these concepts here.

Harmonic Minor

Mood: Royal, Shady

Intervals: W–H–W–W–H–A–H (A meaning augmented for 1½ tones)

Characteristic Keys: Minor Third + Minor Sixth + Major Seventh

Construction: The harmonic minor scale is similar to the natural minor scale, but with a major seventh, i.e. C Harmonic Minor has the same keys as C Minor except that B♭ is replaced with B.

Chords: The triads in C Harmonic Minor are: Cm, Do, E♭+, Fm, G, A♭, Bo. The seventh chords are: CmM7, Dø7, E♭+M7, Fm7, G7, A♭M7, Bo7. There are some additional common chords you can construct in this scale which you can find out in Rick Beato’s video.

Usage: The harmonic minor scale might sound familiar as tonal concepts lead to the minor seventh in the natural minor being sharpened to the major seventh at times to add tension. It has been used historically in Jewish and Eastern European music, currently in Latin music. Famous examples are Britney Spears – …Baby One More Time and Santana – Smooth ft. Rob Thomas.

Characteristic Progressions: i iv V i, i iv viio i.

Melodic Minor

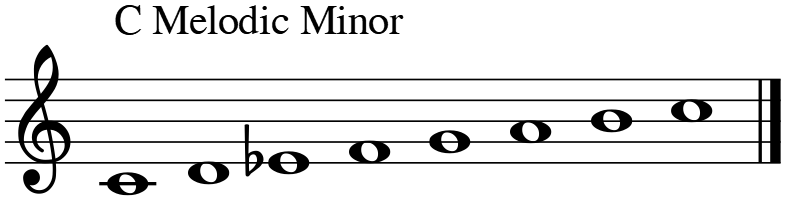

Mood: Mystical, Jazzy

Intervals: W–H–W–W–W–W–H

Characteristic Keys: Minor Third + Major Sixth + Major Seventh

Construction: The melodic minor scale is similar to the natural minor scale, but with a major sixth and major seventh, i.e. C Melodic Minor has the same keys as C Minor except that A♭ is replaced with A and B♭ is replaced with B. It can also be thought of as the harmonic minor scale with a major sixth, the Dorian scale with a major seventh or the Ionian scale with a minor third.

Chords: The triads in C Melodic Minor are: Cm, Dm, E♭+, F, G, Ao, Bo. The seventh chords are: CmM7, Dm7, E♭+M7, F7, G7, Aø7, Bø7. There are also additional chords, but I could not locate a good source with this information.

Usage: Some versions of the English folk song Greensleeves, which shares its melody with the Christmas song What Child is This, use a combination of natural minor, Dorian and melodic minor.

Most classical composers only apply this scale to ascending phrases and use natural minor for descending phrases (ascending melodic minor) but jazz composers use it for both, giving it the alternate name “jazz minor”.

Characteristic Progressions: This scale has so many unique chord progressions that you can just go wild.

Composition

Some modern composers (save for jazz, of course) find that modal concepts are dated since tonal concepts intrinsically incorporate multiple modes. For this reason, they discourage learning about individual modes, but I beg to disagree. Tonal concepts are as empowering as modal ones are liberating. Improvising with each mode on its own allows us to discover its unique feel, allowing us to imbue a particular vibe into a composition through various combinations of moods. Combining tonal and modal concepts will give you a compositional freedom that can still sound amazing.

I will first discuss the well-established technique of modal interchange, then 2 ideas which I have found useful when composing. These ideas are definitely not new or groundbreaking, but they are my attempts to formalise them to make them easier to understand and use.

Modal Interchange & Modulation

Ever wondered why the Fm or B♭ chord sometimes works in C Major/Ionian, even though neither are in the key? The idea behind it is modal interchange (or mode mixture). Modal interchange and modal modulation are quintessential concepts when writing melodies with modes.

I shall use the following definitions to distinguish between the two concepts:

- Modal Interchange: The act of changing the scale while preserving the tonic key (includes borrowed chords). Equivalent to parallel key modulation but not mode shift. Examples:

- A Aeolian to A Phrygian

- E♭ Dorian to E♭ Melodic Minor

- Modal Modulation: The act of changing the tonic key while preserving the scale. Equivalent to transposition. Examples:

- C Ionian to A♭ Ionian

- A♭ Dorian to C♯ Dorian

- A relative key modulation, which is the act of changing the scale and tonic key while preserving the key signature, is the combination of a modal interchange and modal modulation. Examples:

- B Locrian to E Phrygian

- F♯ Mixolydian to E Lydian

Here I define modal interchange to allow interchanging from scale X to scale Y where X and Y are not modes of each other, making it different from mode shift. I will not discuss techniques for modal interchanges and modulations but more on how to apply them to compositions. Some observations that I have learned:

- After interchanging or modulating, you can establish the new scale/key by using its characteristic chords/progressions. Relative key modulations rely on progressions with strong tensions that resolve to the new tonic. Resolution by half-step is a good method for this.

- Modal interchanges have a slight preference towards the direction of darker → brighter. Darker means more flattened keys in the scale, and brighter means more sharpened keys; they don’t necessarily mean more dissonant and more consonant. The minor scale variants and Picardy third are good examples of this.

- Interchanging between scales with similar moods (e.g. Phrygian & Harmonic Minor) is usually smoother than between scales with contrasting moods (e.g. Ionian & Locrian). This doesn’t mean that contrasting moods should be avoided though!

The second point is especially important when selecting the primary scale for your composition. Selecting a consonant scale such as Ionian might make for an easier process but limit your scale options. Selecting a dissonant scale such as Locrian requires meticulous care but has high potential for modal interchanges. If you’ve ever composed a tonal piece in minor, you’ve already been using a combination of Aeolian, Harmonic Minor (V or V7) and Melodic Minor (viio or viiø7) whether you realised it or not!

Example

Take an example of composing in C Ionian. Say, for a phrase of 4 bars, you only use the following keys: C, D, E, G, A. There are some other modes containing those keys, which are Lydian and Mixolydian. You can then use chords from any of those modes instead of purely Ionian chords. For example, instead of Bo, you could use Bm or B♭.

Take a more complicated example of composing in C Phrygian. In a phrase, you only use the following keys: C, D♭, E♭, F, G. Although no other scales I’ve discussed have these keys, you can actually use chords from Aeolian, Dorian, Harmonic Minor and Melodic Minor that do not contain the D key.

Modal Uncertainty

I decided to explore the idea of modal interchange by drawing a link to the concepts of modes in quantum mechanics (eigenstates), namely on uncertainty and superposition. What I realised is that you are not always composing in a single scale or mode, but instead multiple scales at the same time, determined by the keys you choose to use in a particular phrase. This is some kind of modal uncertainty, where you are in a combination (superposition) of several modes.

In the earlier example of using the keys C, D, E, G, A, you might have noticed that this scale has a unique Bittersweet, Longing mood that is quite different from Ionian, Lydian and Mixolydian. You might have also noted that those 5 keys constitute the C Major Pentatonic scale, used extensively in traditional Chinese music, which you would’ve come across if you’ve tried playing only the black keys on a piano with D♭ as the tonic.

This is a rather interesting insight as we did not introduce any new keys but instead omitted some, yet this scale has a very different feel. What this means is that by enforcing an ambiguity within the {Ionian, Lydian, Mixolydian}, we’ve introduced a new mood! You can experiment with introducing ambiguity to unearth more useful moods.

Example

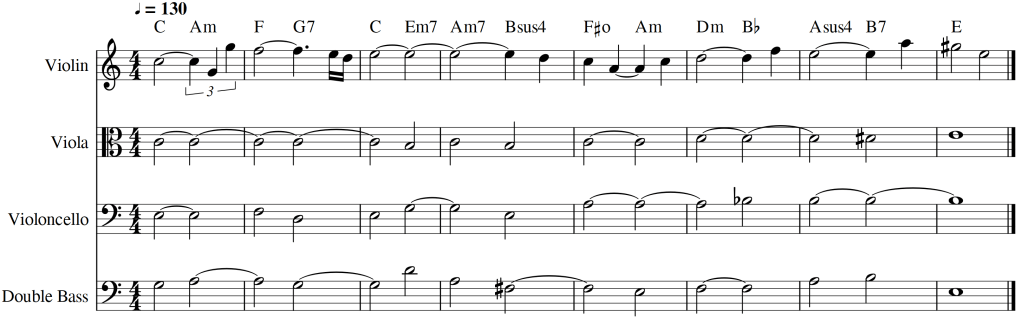

In this example, I wrote a short and simple 4-part harmony purely in the modern modes. Mind that I’m no expert on part writing, and this is only a proof-of-concept. I could also have been more thoughtful about the inversions I used. The harmonic rhythm used was 2 beats per scale degree.

In this composition, I wrote the melody first followed by the harmony. Note that bar 1-7 can be harmonised entirely in C Ionian.

- Bar 1-4: I included the perfect fourth F and major seventh B in the melody to emphasise the Ionian mode. I harmonised in C Ionian with a simple, functional progression.

- Bar 4-5: I omitted F and B in the melody for an uncertainty of (Ionian, Lydian, Mixolydian). I decided to harmonise in C Lydian.

- Bar 5-7: I omitted F in the melody for an uncertainty of (Ionian, Mixolydian). I decided to harmonise in C Mixolydian.

- Bar 7-8: I wanted to follow through with the ascending structure to maintain the tension and give a small twist ending. To do this, I decided to modulate up a third to E and harmonised in E Ionian.

In bar 4, I interchanged from C Ionian to C Lydian using Am7 as the common chord, following up with Bsus4 and F♯o which were unique to C Lydian to establish the mode.

In bar 5, I interchanged from C Lydian to C Mixolydian using Am as the common chord, following up with Dm and B♭ to establish the mode and to continue the ascending motif in the middle voices.

In bar 7, I modulated from C Mixolydian to E Ionian. This was slightly tricky as they only have 2 keys in common: E and A, and the chords of those 2 keys are different in each scale. C Mixolydian has Eo and Am, whereas E Ionian has E and A. I decided to use Asus4 as the common chord since it did not require the third, which worked out well.

Modal Hybrids

Knowing that there are 12 semitones in an octave, how many ways can we choose 7 keys to form a scale, if we don’t consider transpositions to be distinct? This involves some nasty combinatorics of bracelets which I won’t go into. According to this answer, there are 266 possible heptatonic scales in total, and yet we’ve only covered 9 of them! Of course, I doubt it’s realistic to get familiar with all of them, but one trick we can use is to hybridise known scales into new ones. This actually brings us closer towards tonality.

For example, consider the following scale in C: C, D♭, E♭, F, G, A♭, B, C. This is a scale we’ve never seen before, but what can we say about it? The first thing to notice is the minor second + perfect fifth, implying a Phrygian mood on the second to fifth. The next thing to notice is the minor third + minor sixth + major seventh, implying a Harmonic Minor mood on the sixth to seventh. What we have here is thus a hybrid of Phrygian and Harmonic Minor, and we can shift the emphasis by focusing more on the first 5 or last 3 keys. On a side note, this is a fairly popular scale, known as the Neapolitan Minor.

We can introduce modal uncertainty in the above example by omitting the A♭ key. This implies a combination of Harmonic Minor and Melodic Minor on the sixth to seventh. We then end up with a hybrid of Phrygian and the {Harmonic Minor, Melodic Minor} combination.

This works well for scales with a minor third, as the Phrygian and Locrian moods are largely dependent on the choice of second to fifth keys, and the Dorian, Harmonic Minor and Melodic Minor moods are largely dependent on the choice of sixth to seventh keys. You can pick and mix any of these to construct your desired scale.

If you’re composing in blues or jazz, this technique might not be of much help as you are free to use the entire chromatic scale.

Example

In this example, I experimented primarily in the Locrian scale and composed a short D&B snippet, while at times incorporating the major sixth, major seventh, or both. This made those parts a hybrid between Locrian and {Dorian, Harmonic Minor, Melodic Minor}. Interestingly, using the major sixth in Locrian results in Locrian ♮6, a mode of the harmonic minor scale. In the short oriental section, I omitted the third and sixth of the Locrian scale, giving the Iwato scale, used in Japanese koto music.

Locrian has this persistent tension (more so than Aeolian) which makes it terribly unsettled on its own. However, this made it a great canvas for me to add moods from other scales, such as when temporarily interchanging to a more consonant scale for a more resolved tonality, which sounded incredibly satisfying. Check out the track: