This is the first out of two posts delving into the physics and mathematics behind what makes music work. In this post, I will discuss the nature of what sound is, and where it gets it properties from. Let’s start by asking the rudimentary question, “what is sound?”

Sound is Moving Air

Let’s try a simple exercise; try to talk with your breath held. If you have tried this out, you would notice that this is impossible. We must definitely inhale or exhale as we speak, and so:

- Sound requires movement of air.

For the next exercise, try to hold an “ah” sound and vary the strength you use to exhale in the process. You might notice that by breathing more heavily, your voice becomes louder. This brings us to the next observation:

- The loudness of a sound is related to the speed of the moving air. The greater the speed, the greater the loudness.

Now, try to make the lowest pitched sound you can muster, and then the highest. As you are doing so, pay attention to your chest. You might notice that when you speak deeply, your chest vibrates much more than when you speak gently. Alternatively, you might have tried blowing air across the mouth of a bottle or sliding a finger across the rim of a wine glass to produce a humming sound. Notice that having more liquid in the bottle/glass results in a higher-pitched hum. Hence:

- The pitch of a sound is related to the volume of the moving air. The greater the volume, the lower the pitch.

We are still missing one more key property of sound. Try playing a note on your favourite instrument and singing that note at the same loudness. Do they sound the same, or different? You might also have tried the fun experiment of inhaling helium and noticing your voice sounding higher. This is the tone’s quality, or its timbre. It is what gives each instrument its characteristic sound, and it depends on what the sound travels through. Our last observation is:

- The timbre of a sound is related to the medium (air, helium, wood, steel, etc.) and shape of the medium it travels in.

Of course, now we need to discard the idea that sound is moving air, since it can also be moving helium or some other medium. What we can keep is the idea that sound is a movement.

Sound is a Vibration

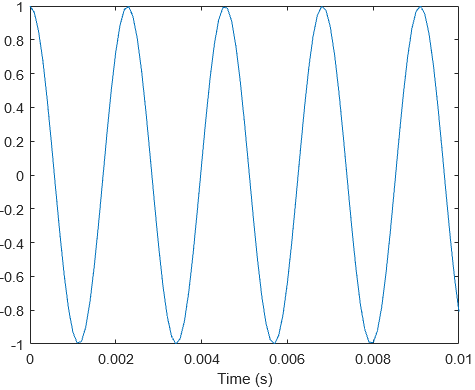

A vibration, in essence, is a wave. Firstly, take a look at the simplest kind of wave, a sinusoid (or sine wave). Sounds of tuning forks have this waveform.

A sinusoid in time has 3 basic properties:

- Amplitude (

): The peak value of the sinusoid. Also known as magnitude.

- Frequency (

): The number of cycles in a given span of time.

- Phase (

): The offset of the sinusoid relative to some given point in time and space.

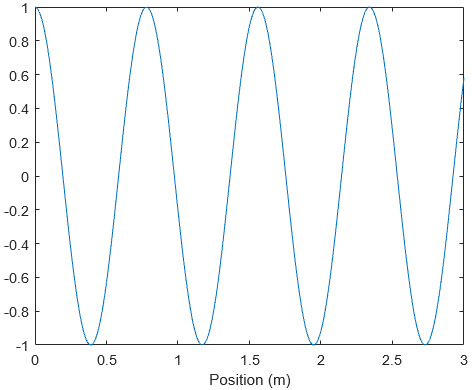

In the above image, the amplitude is 1, frequency is 440 Hz and phase is 0 rad. However, a sound wave is a travelling wave, which means it’s not just a wave in time but also a wave in space. A sinusoid in space looks exactly the same in time, just that the axis of time is replaced by the axis of position.

A sinusoid in space has 3 basic properties as well:

- Amplitude (

): Same as the amplitude of a sinusoid in time.

- Wavelength (

): The length of one cycle.

- Phase (

): Same as the phase of a sinusoid in time.

In the above image, the amplitude is 1, wavelength is 0.78 m and phase is 0 rad. We need some way to relate the temporal part of the sinusoid with its spatial part. The quantity that will help us do this is the speed of sound in air (), which is fixed at 343 m/s. The important relation is: velocity = frequency × wavelength (

).

Now, to relate these properties of waves to the properties of sound.

- Loudness: If we let the sinusoid represent the velocity of air at some point in space, then we can immediately see that the amplitude is related to the loudness. More accurately, loudness is the intensity of the wave, related to the power density, which involves some rather detailed physics. We can also alternatively let the sinusoid represent the air pressure for a related formulation, but these will not be discussed here.

- Pitch: Since pitch is related to the volume of air, a longer wavelength corresponds to a lower pitch. Notice that according to the relation between wavelength and frequency, a wave with long wavelength has a low frequency, and a wave with short wavelength has a high frequency. Hence, the pitch is related to the frequency. More about this later.

- Timbre: Two sinusoids with the same loudness and pitch will always sound the same. This means that all sinusoids have the same timbre, which is inherent in the fact that they are sinusoids.

In order to understand timbre, we need to look at a more complicated waveform and give it the name “Waveform A“. Firstly, listen to the tone of waveform A:

https://soundcloud.com/user-563566793/waveform-a/s-uWPo0

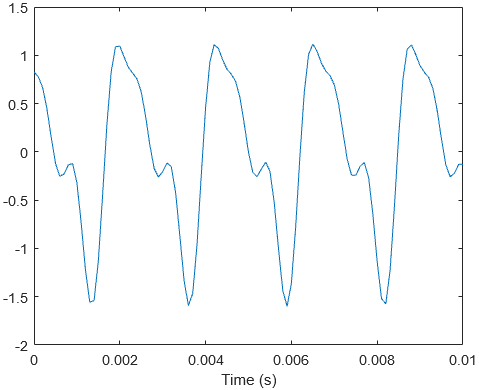

Notice that it has a definite pitch, and thus some associated frequency. This is not like white noise or drum kicks, which have indefinite pitch. Now, lets look at the waveform itself:

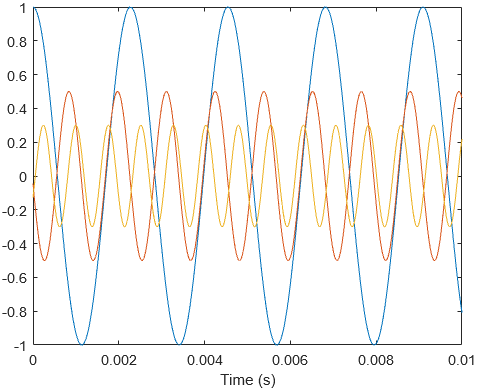

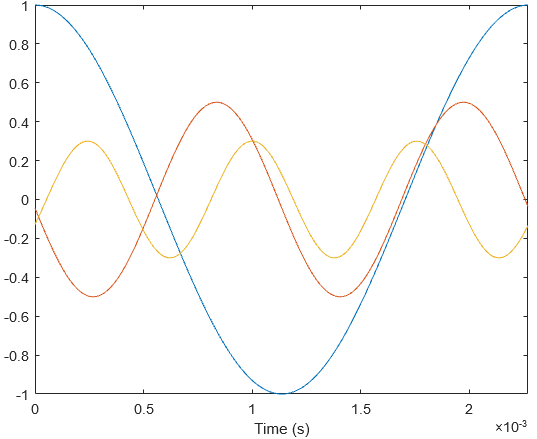

For now, let’s only look at the temporal part of the waveform. What is its amplitude, frequency and phase? That’s not an easy question to answer since it has such an irregular shape, but there is a crucial observation to make about the waveform: it repeats itself every 0.002 s or 0.78 m. This means that it’s periodic with frequency 440 Hz, and any tone with definite pitch also contains multiples of the frequency. We can use a very powerful tool to study any periodic waveform: the Fourier Series.

The Speed of Sound

Before moving on to the Fourier Series, I would like to highlight here that the speed of sound is fixed, depending on the medium and its temperature. Stiffer and hotter mediums have a higher speed of sound, softer and colder mediums have a lower speed of sound. The speed of sound in air at room temperature is about 343 m/s.

Some of you may be wondering; if the loudness and pitch of sound depends on the speed of the moving medium, then why is the speed of sound in that medium fixed? To explain this point, I will use air as the medium. We need to know what the air particles are doing. Take a look at the image below which shows how a sinusoidal sound wave travels in air:

- Firstly, pay attention to the dark regions. These are the peaks of the sound wave in space, moving towards the right. They travel at the speed of sound.

- Next, pay attention to the red dots. These are the air particles in space, vibrating in place. Their vibration speed depends on the loudness and pitch of the sound.

This is the same principle of how electric current travels in a wire; the vibration of the particles cause a perceived effect of a wave travelling to the right, and nothing physical really travels with the wave.

- Increasing the loudness will lead to darker regions (and consequently, the regions in between them will get brighter).

- Increasing the pitch will lead to smaller gaps between dark regions.

- The dark regions will always travel at the same speed.

Taking Apart Sound Waves

Without going into any detailed mathematics, the Fourier Series works on the rationale that any periodic waveform can be decomposed into sinusoids (these waveforms need to fulfil certain criteria known as Dirichlet conditions which I will not discuss). What this means is that I can add individual sinusoids to construct the waveform. Waveform A can be expressed as the sum of 3 sinusoids/components:

Below is a zoomed in version for easier viewing:

We can make the following important observations about each component:

- The blue component has the lowest frequency (440 Hz), which corresponds to the period of waveform A.

- It has an amplitude of 1.0 and a phase of 0.00 rad.

- The red component’s frequency is 2 times of the blue sinusoid’s (880 Hz).

- It has an amplitude of 0.5 and a phase of +1.66 rad.

- The yellow component’s frequency is 3 times of the blue sinusoid’s (1320 Hz)

- It has an amplitude of 0.3 and a phase of -2.01 rad.

The frequency of waveform A is called its fundamental frequency (), and the component with that frequency is its fundamental. All higher frequencies are always integer multiples of the fundamental frequency, and those components are called the harmonics. The component with 2× the frequency is the first harmonic (

), the component with 3× is the second harmonic (

), and so on. All components need not have the same phase.

For sound waves, the pitch refers to the frequency of the loudest component (i.e. largest amplitude). Typically, the fundamental is the loudest, making the fundamental frequency the pitch. However, there are cases where the fundamental and the even harmonics are so soft that they are unnoticeable. For practical purposes, the first harmonic can be considered as the fundamental and all odd harmonics as the harmonics themselves.

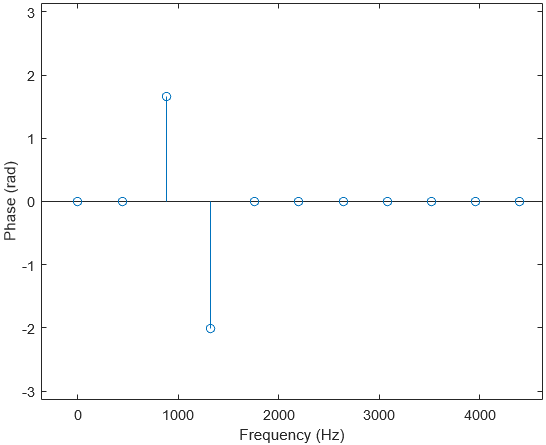

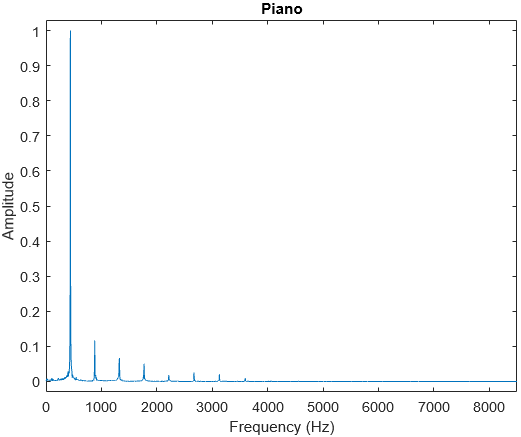

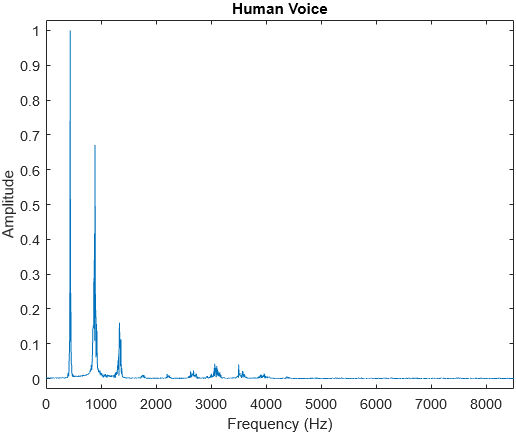

For the timbre, we need to visualise the waveform differently. Instead of representing the waveform as the velocity of air over time, we can represent the waveform as the velocity of air and its phase at each frequency. This is known as the waveform’s frequency spectrum:

The timbre is the combination of these two properties:

- The ratio of amplitude between each harmonic and the fundamental.

- The difference in phase between each harmonic and the fundamental.

The timbre is said to be brilliant if the higher harmonics have large amplitudes, and mellow if the higher harmonics have small amplitudes.

Analysing Common Tones

I have used 440 Hz in the earlier examples for a good reason. This frequency is, by international standard, the frequency of the middle A note (A4) for all instruments.

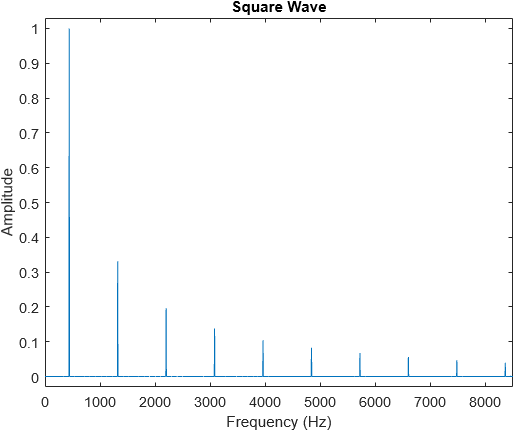

For digitised audio in computers, the waveforms are not continuous but instead come in the form of audio samples. The technique used to decompose samples into frequency components is a well-known one called the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). The FFT is used heavily in audio processing, which I may cover with other frequency analysis techniques in a future post. I only plotted the amplitudes of the harmonics as it is of greater interest than the phase.

Below are examples of 4 simple 440 Hz synthetic waveforms as well as some common instruments playing a 440 Hz note. The synthetic waveforms were generated with a tone generator, and the instrument sounds were generated synthetically using the free composition software MuseScore.

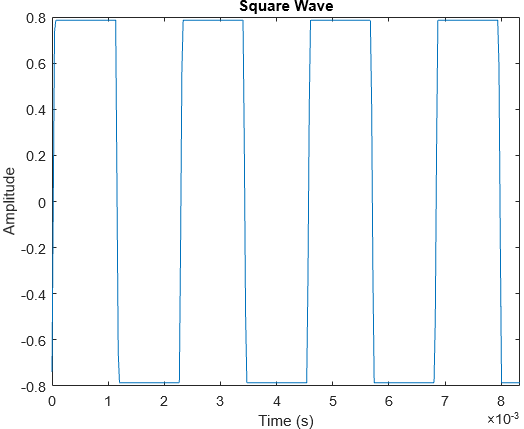

Synthetic Waveforms

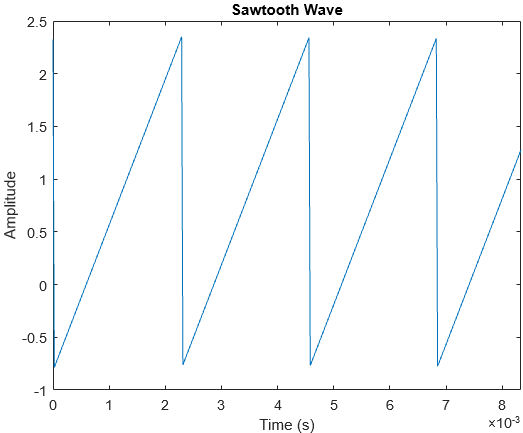

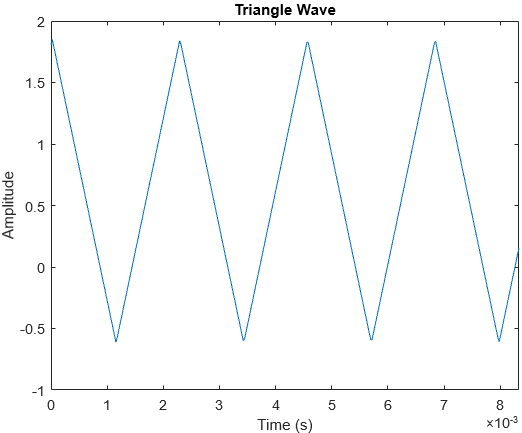

These are the frequency spectra of 4 well-known synthetic waveforms: sine waves, square waves, sawtooth waves and triangle waves. These were all generated with a tone generator.

Sine waves are very common in nature, and they have the mellowest timbres possible.

Square waves only have odd harmonics due to the symmetry of each cycle. They also have a rather artificial timbre.

Sawtooth waves have the same odd harmonics as square waves, but also have even harmonics. They also sound artificial. The tiny peaks at the bottom of the frequency spectrum are likely due to spectral leakage since I used a rectangular window. I may explore this in a future post.

Triangle waves also have symmetry in each cycle, and hence only have odd harmonics. They sound more natural.

Instruments

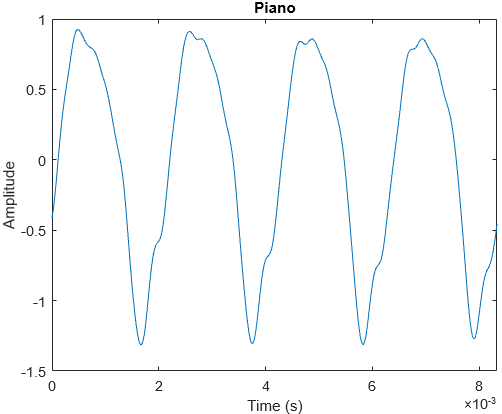

Pianos are percussive, so they have a sharp attack and decay, as well as short sustain. Only the sustain region was analysed. Interestingly, a piano’s sustain waveform is very sinusoidal as its harmonics have very low amplitudes compared to the fundamental.

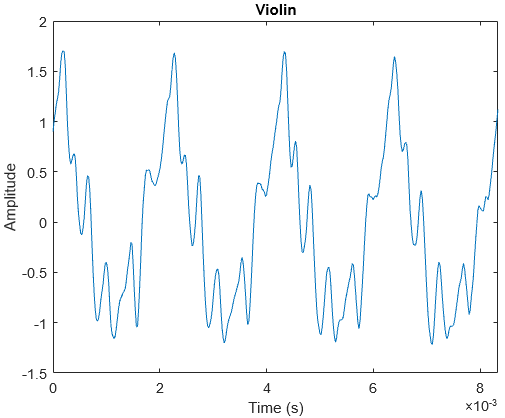

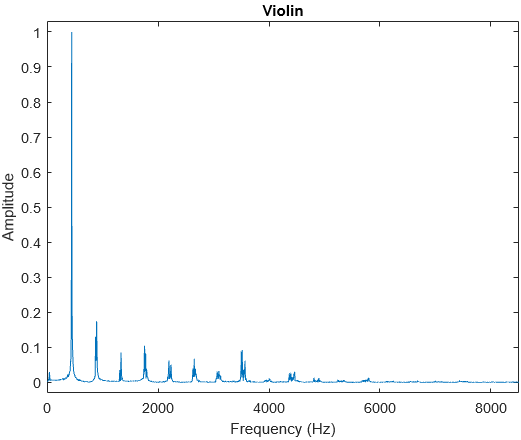

Violins can be plucked or bowed. In this example, I only analysed a bowed violin. The harmonics of a bowed violin have noticeable amplitudes, giving it a more complicated waveform than the piano.

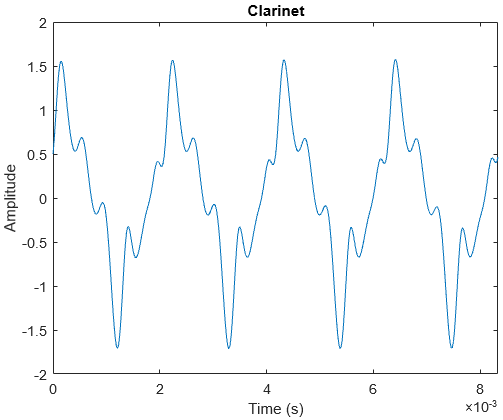

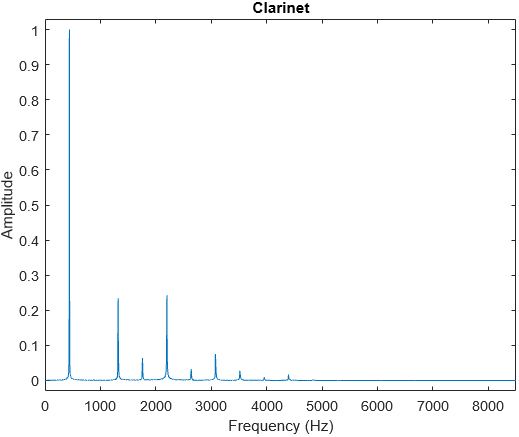

Clarinets have several tunings, the most common being A Clarinets (C = 440 Hz) and B♭ Clarinets (C = 466.164 Hz), each with its own orchestral function. Here I analysed an A Clarinet playing a C note. A clarinet’s waveform is very similar to a violin, but with smaller amplitudes for higher harmonics, leading to a mellower timbre.

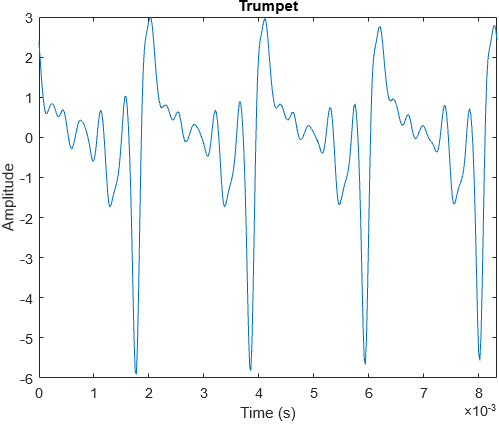

Trumpets have the most brilliant timbres out of all instruments so far. Without looking at its waveform and frequency spectrum, it is not hard to imagine how they would look like. We can expect higher harmonics to have larger amplitudes, and the waveform to have many sharp corners.

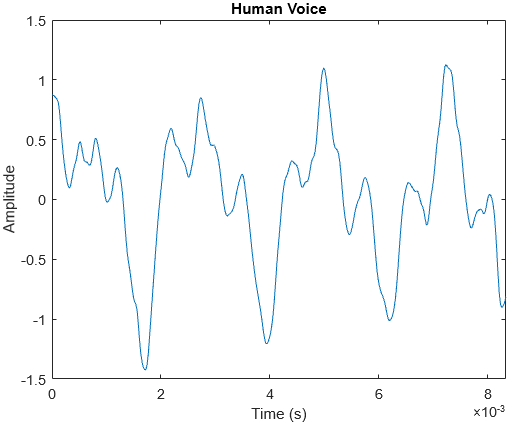

For human voices, vocal cords are made of soft tissue, unlike musical instruments which are usually made of stiffer materials. As a result, they have very irregular waveforms which change slowly over time without settling. The frequencies of human voices also fluctuate slightly over time, and so its spectrum tends to be more smeared.

Perceived Pitch

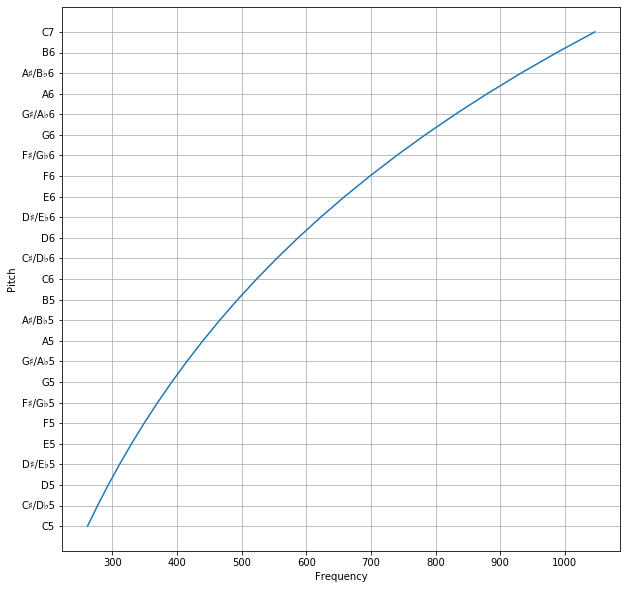

Earlier, I mentioned that frequency is related to pitch. While this is correct, it does not give the full picture. In order to understand their exact relationship, we need to look at how octaves work.

An octave is defined to be a factor of two in frequency. An octave up is defined as double the frequency and an octave down is half the frequency. It has the confusing prefix “octa-” as it refers to the eighth white key from another key, but should not be taken to imply some factor of eight. For example, since middle A is defined to be 440 Hz, tenor A is 220 Hz and treble A is 880 Hz.

At this point, you might be confused. To our ears, tenor A sounds as far away from middle A as treble A. We also know that there are 12 semitones between tenor A and middle A, as well as between middle A and treble A. However, tenor A to middle A takes up the frequency range of 220 Hz – 440 Hz (220 Hz difference), and middle A to treble A takes up the frequency range of 440 Hz – 880 Hz (440 Hz difference). So how is it that the same number of keys covers a different frequency range?

To answer this, we must know how our ears perceive pitch. It has a similar mechanism to how our eyes perceive brightness. Take a look at the image below:

This image contains 4 different shades. On the left is black with 0% brightness, on the right is white with 100% brightness, and in the middle are 2 different shades of grey. Which shade of grey looks like it is exactly between black and white? Through our perception, it would seem that the one on top is in between, and the one below is closer to white.

However, the shade on top has 33% brightness, and the shade below has 50% brightness, meaning that our perceived brightness is not the same as the actual brightness. Our eyes actually discern differences in brightness for darker shades better than lighter shades.

In a similar way, our ears also discern differences in pitch for lower frequencies better than higher frequencies. You can try it yourself with a tone generator: listen to 200 Hz, 220 Hz, 2000 Hz and 2020 Hz. You will notice that the pitch difference between 200 Hz and 220 Hz is greater than the difference between 2000 Hz and 2020 Hz. Hence, pitch is related to frequency, but with a different scale.

The Logarithmic Scale

Pitch is frequency on a logarithmic scale. What this means is that adding to the pitch is equivalent to multiplying to the frequency, and subtracting from the pitch is equivalent to dividing from the frequency. For example:

- To add an octave to the pitch, you multiply the frequency by 2.

- To subtract an octave from the pitch, you divide the frequency by 2.

- To add a semitone to the pitch, you multiply the frequency by about 1.0595.

- To subtract a semitone from the pitch, you divide the frequency by about 1.0595.

- The exact value to multiply/divide by for a semitone is

.

In the image below, you can see the frequencies of notes in 2 octaves (middle C to high C). The formula is , where

is the frequency of the note, and

is the number of semitones the note is above middle A.

Note that aside from the octave, all keys here use the 12-Tone Equal Temperament system, which I cover in greater detail in my next post.

Natural vs Artificial Sounds

Earlier, I mentioned that sine waves and triangle waves sound natural, and square waves and sawtooth waves sound artificial, but I did not explain why. To understand the reason, we must first understand how sounds travel through media.

There are 2 processes that occur to sound as it travels through media:

- Point Radiation: Sound radiates outwards from a source, and its power becomes spread out over a progressively larger area the further it radiates. This causes its power to decrease (i.e. it becomes softer) the further it travels.

- Acoustic Attenuation: Even if you confine the sound to travel along a single direction (e.g. tin can telephone), its power will still decrease as it travels, mainly due to friction in the medium. A medium like this is a lossy medium. Most natural materials are lossy media; brittle materials are more lossy, and flexible materials are less lossy.

The important point is that for point radiation, the power loss does not depend on the frequency of the sound. However, for acoustic attenuation, power loss depends on frequency: lower frequencies lose less power than higher frequencies. Physically, what this means is that it is easier for lower-pitched sounds to travel through media than higher-pitched sounds.

Let’s try another exercise. Try talking normally first, then talking with your hand covering your mouth. Notice how when your mouth is covered, your voice is softer, and the lower pitches are more prominent than the higher pitches. I shall refer to this as muffling. Muffling occurs because of acoustic attenuation. You can also hear this effect by playing a square wave tone, using your hand to cover the speaker, and noticing how it sounds more like a triangle wave.

Hence, in this sense, lower pitches occur more naturally than higher pitches. Our ears are more used to hearing lower harmonics than higher harmonics. By the same logic, natural sounds would have harmonics with amplitudes that decay quickly (mellow), and artificial sounds would have harmonics with amplitudes that decay slowly (brilliant). This plays a big part in consonance and dissonance, which I will discuss in the next post.